Thinking Locally

Hold more than a cursory conversation with a Liberal Democrat, particularly one who has been involved in the party since before the Coalition, and you’ll almost certainly hear them extol the virtues of “community politics” as the party’s salvation and bedrock. The principle of embedding deeply into our communities and becoming supremely concerned with potholes, bin collections and community petitions has won us thousands of council seats over the years, and is frequently seen as crucial to our capacity to come back from national defeats. If we retain a strong local base through community activism, the logic says, we can hold on until the next election and convert that into national success.

This logic is not necessarily wrong. Clearly, being a party with a wealth of activists, active local volunteers, and a less overbearing federal party has its advantages, and has helped our survival since wipe-out in 2015. But increasingly, I fear it is not sufficient for our success, and is in fact becoming an obstacle to it. The survival tactic has been internalised as a catechism of liberal ideology, harmful because the tactic is itself so bereft of any real liberalism at all. And lately, the logic has been reversed. In our most recently won national seats, it is not because of strong local council bases that we were victorious, but rather, we won strong local council bases after taking back those seats (think Oxford West and Abingdon, where we stormed to victory last year two years after Layla Moran’s initial victory; or Bath, where we sensationally seized control from the Conservatives two years after Wera Hobhouse’s win).

My central argument here is that while survival is good, thriving is even better – and in order to thrive, we need to regain a sense of liberal vision, which, I argue, we have lost over the past few decades. With the flatness of our efforts over the past few years, and with our potentially necromancing issue (Brexit) now settled, we need an ideological revival. Local councils seem the best place to start this for two reasons: first, we actually control several of them outright, and so we can practise what we preach; and second, there are local elections coming up, so we can implement this more quickly.

The problems

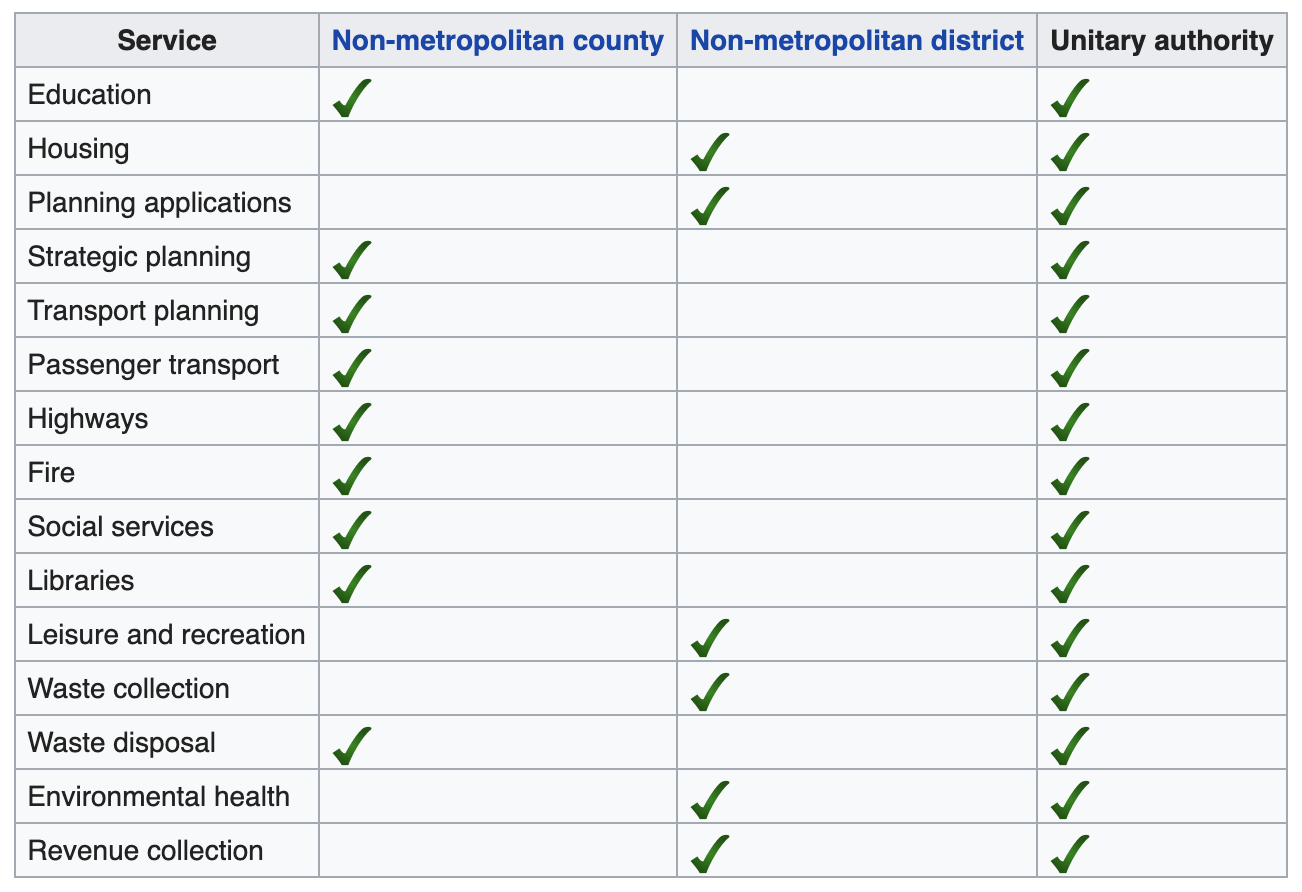

At present, there is a litany of problems with our approach to local politics. Some of them are external, and beyond our control – for instance, local authority powers are limited, and in many cases reliant on funding from central government which is particularly unforthcoming at present. And the public often has a particular set of expectations as to what the function of a local authority is, and acting outside that set of expectations may be controversial. But many of our problems are internally created: a lack of imagination about what to do with the powers we have, and a general confusion as to what liberalism means and how we can practically implement it.

This latter problem is particularly acute. I may largely disagree with the conclusions that were drawn from it and implemented under the Coalition government, but the Orange Book era was the last time a coherent philosophy was motivating the party. Since 2015, it has seemed at times that we have had nothing to say, no broader vision for what the country would look like under a Liberal Democrat government. Our over-reliance on principles of common sense and ‘evidence’ (which, while comforting, can only ever provide half of the picture: once we collect evidence, our response to it must be governed by our political philosophies, ie our ideology) along with tightly-managed and focus-grouped national campaign messages have replaced values-based campaigning and the policy we derive from those values. Buzzwords drawn from the preamble to the Constitution are not enough – we need to have a discussion as a party about what we mean when we say we are liberal.

For my money, the core of liberalism is that it must be transformative. If it is not transformative, it has lost its essential essence – that radical opposition to conglomerations of arbitrary and unchecked power which transformed the world in centuries past. Liberalism which rests on its laurels or believes that it has ‘won’ or that the status quo is largely acceptable not only fails to recognise how broken our society and our economy are, but is in danger of sliding into privileged conservatism.

In my experience, much confusion lies in an essential misconception about what liberal politics means: it is the difference between personal liberalism and political liberalism. Personal liberalism is an attitudinal thing – it is personal tolerance and acceptance and permissiveness of things that we might ourselves disagree with. Political liberalism, however – the subject matter of politics and the end goal of us as a liberal party – is a matter of statecraft, and is concerned with ensuring that the government observes neutrality – that the rule of law is strong, that no group is preferred or discriminated against by the state, and that freedom is advanced on a societal basis. It is political liberalism that we should concern ourselves with – essentially, the question of what government should do to further freedom and non-discrimination.

Within political liberalism, we can distinguish further. Political liberalism is concerned with both means and ends. That is, political liberalism requires that politics be both procedurally liberal (means) and substantively liberal (ends). To put it in the simplest terms possible, we have to be liberal in style and liberal in substance.

Bringing it back to localism

Over the past day, I’ve asked different groups of people if they can identify a unique policy or principle of local governance which every Lib Dem council, no matter where it is, implements and adopts. Almost universally, the answer I have received is “nothing specific, but we are more open and consultative”. To be absolutely clear, I think being open and transparent is a fantastic thing – it is clearly of central importance to any democracy. But you will be able to see where I’m going with this – consultation and transparency are matters of style and procedure. They don’t tell us what the decisions themselves are which we’re consulting on or being transparent about. We are thus still left without an account of what liberals substantively believe in.

Why is this a problem? Very simply because exclusively procedural accounts of liberalism render us vulnerable to objections that we in fact don’t have any substance, or that we are ambivalent about the actual substantive decisions so long as liberal process has been observed. Liberalism cannot be as hollow as merely carrying out what local residents want, no matter how illiberal. It would render our ideology empty – we wouldn’t be standing for anything ourselves. That cannot be right.

And it isn’t right. Clearly, liberals do not have merely procedural goals. We are liberals because we have shared beliefs about what government should and should not do, and those beliefs are motivated by our political ideologies. For instance, liberals almost universally object to police overreach, to the use of indiscriminate facial recognition technology, to fining the homeless by abusing public space protection orders. These examples illustrate that we can and do have shared beliefs, motivated by liberal ideology, about what local government should substantively do. We just need to be more imaginative and unique, and be louder about these beliefs when we campaign.

Bringing it all together

“Harry, you’re mouthing off about political philosophy again,” I hear you say. So let me put this all into practical terms.

We should retain the good local stuff we’re doing already. Lib Dem councillors will always be best at making sure potholes get filled, bins get collected, and that communities are empowered. We will always ensure that consultations are carried out, that the public are engaged with (even if we disagree with some of them) and that information is circulated.

But let’s also be bold in having a local, liberal agenda to transform the lives of people living in the authorities we control, and make sure society works for them.

We should be the pre-eminent party of affordable housing and liveable towns and cities. This means insisting on affordable and social housing being present at volume in all housing developments. This means putting environmental considerations at the heart of all developments. This means discouraging car use through cycle and pedestrian friendly design, and expanding and cheapening public transport.

We should be the party of eradicating homelessness. This means taking the lead of Oxford and Manchester and constantly, loudly opposing Labour’s fines on the homeless and the use of hostile architecture. This means expanding shelters, and setting up task forces and special services designed to tackle underlying mental health problems and break the cycle of homelessness. We’re already taking a housing-first approach to campaigning on this issue in London with Siobhan Benita: let’s make it a big ticket thing we put emphasis on in all our local campaigning.

We should use 2011 Act powers to set up radical anti-poverty measures. This could include direct payments to those who apply for benefits to ensure they can survive while they wait for their applications to be processed. This could include topping up their benefits. Funding from central government is low and local authorities are cash-strapped, so this is difficult. But where there is a will, there is a way. Poverty is the number one obstacle to economic freedom in this country, and local authorities can take innovative approaches to tackling it.

We should take the initiative and be the party of adult social care. Adult social care in this country is an unmitigated disaster. One of the scariest things for families and care recipients is the prospect of paying for it, often including paying for family homes. We should reduce the minimum contribution by the care recipient to make Lib Dem councils the lowest-charging authorities to be cared for in, and look at alternatives to avoid the outright sale of family properties to fund care under local authorities’ discretionary disregard powers.

We should oppose the use of facial recognition technology. This applies wherever we have councils, and should also form a central part of any police and crime commissioner campaign (which matter and we should take them more seriously).

We should champion the arts. This last one is indulgent of me, but arts programmes often help disadvantaged kids find their niche in the world, and enriched lives are better and freer lives. We should enter into partnerships with the private sector to save cultural amenities threatened with closure like theatres, leisure centres and libraries (which have a huge role to play in providing services for those in poverty), and expand provision of them by building new ones. We can then use our stake in them to ensure cultural activities are cheap and accessible for all.

This is not an exhaustive list. There are more things that can be included. And I’ve not tried to stitch the above into an electoral narrative. But the point is that we should be punchier and more ambitious about our exercise of local power, and make sure that Liberal Democrat councillors and councils stand for something distinctive. It’s not going to happen overnight, or even over the course of one or two electoral cycles, but if over the next decade we can embed in people’s minds that a Liberal Democrat council means a greener, freer, more vibrant local community, with affordable places to live and radical support for those in need, then what is there to lose? Let’s keep the liberalism of style, but be bold and add the liberalism of substance.

Above all, though, let’s reignite a discussion about what liberalism really means when we talk about it. I for one am fed up of the policy soup we have which at election time gets vaguely meshed into a milquetoast document with no punch or overarching vision. There are flashes of brilliance in our manifesto, particularly on criminal justice, the environment, and political reform. Our whole platform can be like that. We need to each ask ourselves why we are liberals, why that matters, and why that makes us different from Labour and the Conservatives (NB not equidistant, but different). We then need to ask ourselves what the roots of our country’s problems are, and how we tear up those roots. We cannot be a bland party broadly fine with the status quo, who tweak a couple of things through extremely specific and technocratic policy. We have to recapture the transformative, revolutionary nature of liberalism, and articulate why it’s not just some weak, highbrow, unambitious thing. Only through conversations such as these will we come up with a consistent and substantive vision, based on our values, that people can really believe in.