We are choosing a new leader. The frontrunners appear to be Layla Moran and Ed Davey, while Wera Hobhouse is also running. One of the major points of discussion is how we deal with the legacy of our involvement in the Coalition. Some in the party, however, have dismissed this concern as being ill-founded, or even self-serving or introspective. But it is in my view still an important factor.

The headline reason is its impact on hindering the national campaign, and the effects of that hindrance further down the chain. To support it, I will use evidence from national media during the 2019 general election, as well as the scant polling evidence we have about voter attitudes towards the Coalition. For good measure, I will then take each major criticism of Coalition concern and establish why those criticisms are poorly founded.

The National Picture

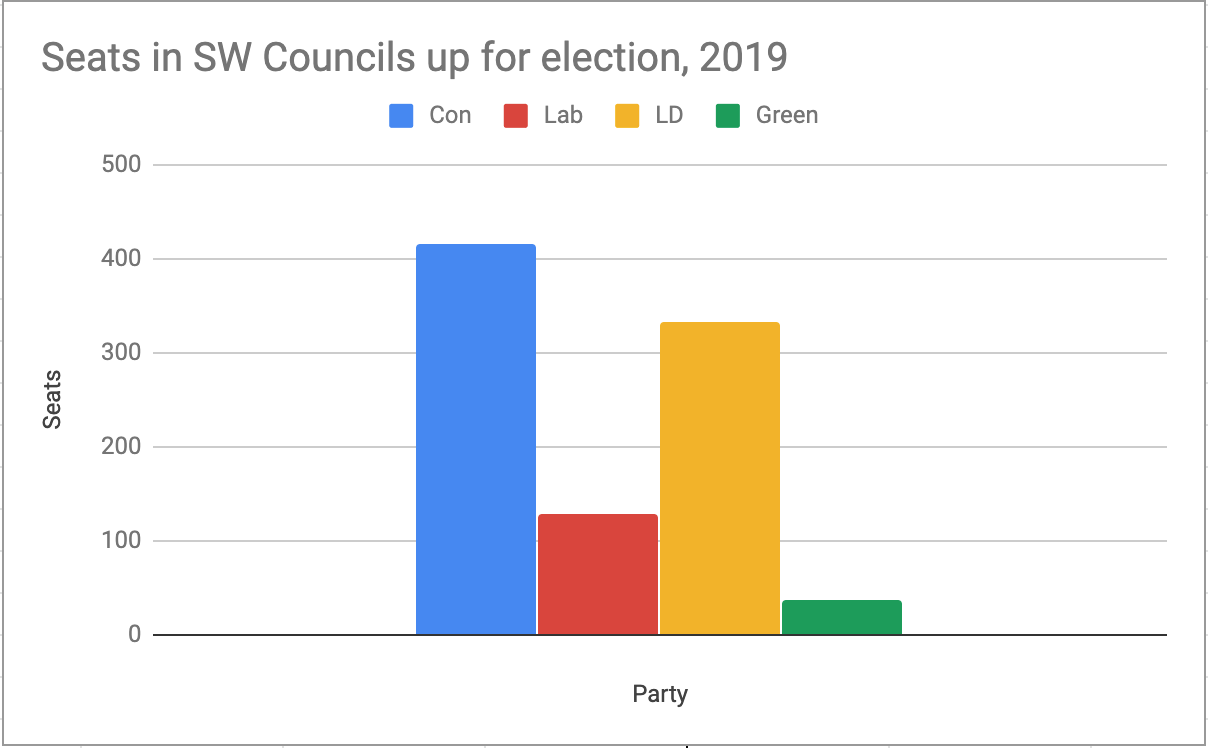

At the 2010 general election, the Liberal Democrats won 23% of the vote. Since then, we have barely broken 11% in a general election. Our popularity in Westminster elections is dismal. Despite the burst of success between the 2019 local elections and European elections, it quickly faded away back into nothing as soon as the national stage became the top priority. That we have grown only 3.7% in half a decade is alarming, and mirrors the doldrums of the postwar/pre-Thorpe era Liberal Party.

There is ample evidence that in a national election, people vote on national issues. In 2019 specifically, YouGov polling showed that of the top 14 issues cited by voters, 10 were wholly national issues, including all of the top five.

National attention is also what buoyed our success in the 2019 European elections. After significant press attention following local election victories, our support swelled to around 20% in those elections, and then up to 24% and first place in the Westminster polls in the weeks afterwards. It is true that our support swells the most in the areas where we have a local presence, but in the absence of any significant, world-record-setting local campaigning in the three weeks between the 2019 local elections and the 2019 European elections, national attention is what must account for the near-doubling of our vote share in opinion polls taken immediately before and immediately after these events. To claim otherwise is to suggest that prior to the 2019 local elections, we weren’t working as hard as after them. In my experience as a member who joined in the dying days of the Coalition and has worked on countless campaigns since, this is not true.

National success lifts us, then. But the same is also true of national failure. In 2015, despite the efforts of local parties across the country, the national picture saw us decimated. In 2017, despite huge new membership, Tim Farron’s views on homosexuality are widely believed to have hamstrung our campaign, diverting press attention away from our message and towards questioning him on the issue. Here we see two types of national failure. 2015 was because of the deep unpopularity of Nick Clegg, the reality that we had broken a promise, and other factors like fear of a Miliband government. This is what I will call “prevailing conditions” national failure. 2017 was because of continued failures of media management and a seemingly continuous stream of questions about an issue we didn’t have an answer to. I will call this “media-based” national failure.

Coalition Questions

The reason national failure can have such an impact is because the vast majority of people receive their political news and information through the national media, consuming political news in very short bursts. The public will glance at a newspaper article either in hard copy or online, and will hear the headlines on the news in the evening. Occasionally, significant media set-pieces will happen, such as TV debates, and these will be watched by a large chunk of the public. It is through these day-to-day snippets and the impression given by politicians in these set-piece events that the public will form an impression of a party and its leader.

Because of the centrality of national media to public opinion, media-based failures are particularly calamitous. The public will see a politician under fire, or dealing poorly with a question, or saying something patently untrue or unbelievable, and will be less likely to want to vote for them. This negative opinion then colours the voter’s reception of local campaigning – if you already think Leader X is a joke with zero credibility, you are likely to have a more dismissive attitude to her party’s leaflets when they come through the letterbox. And, because local campaigning is likely to reach a voter only a very few times over the course of a campaign, local efforts are almost never enough to outweigh the national errors.

This is why Coalition is so dangerous an issue, because it has the potential to be a serious media-based failure. A leader who cannot deal adequately with questions about Coalition, about trust, about voting records, about austerity, about hypocrisy in the national media will be viewed as incompetent and unserious by the public at large, and local campaigning will be treated less favourably as a result.

This is a point which Coalition concern sceptics often ignore. They say that they don’t hear the Coalition come up on the doorstep, and thus imply that the doorstep is all that matters. But that is not true. Election campaigns are not simply the aggregate of every voter spoken to individually on a local level, as I have demonstrated above. And even if voters don’t bring it up specifically, poor responses to the Coalition question will still colour their perception of the basic competence and viability of our party. In short, even if a voter doesn’t expressly say “I don’t trust you because of the Coalition”, that doesn’t mean our leader’s response to tough questions about the Coalition doesn’t influence how they perceive the Liberal Democrats.

And this is borne out by the evidence. It is obvious that a significant number of our 2010 voters abandoned us. The last polling done asking them why they haven’t returned to us was carried out in 2017. It found that for 38% of them, their top reason was the Coalition. This is more than double the next most prevalent issue, that voting Lib Dem would be a wasted vote. Things may have changed in the three years since, but it would be surprising if that 38% figure had suddenly plummeted. These are voters who have voted for us in the past, not hard-line socialists who would never even contemplate us. We can win them back – but to do that we have to acknowledge what is keeping them away. Denying that the Coalition is still an issue which impacts upon our party’s success is surely untenable.

2019: A Case Study

A perfect illustration of the continuing importance of the Coalition to the national campaign is the 2019 general election. Four years and two leaders later, I remember hoping that this might be the first election where it wouldn’t come up as much, and we would be able to move on. But I was wrong.

The 2019 general election was officially called when legislation permitting an early election received Royal Assent on 31 October 2019. Between that date and the general election, there were 41 days. Going back through national media pieces about the party and Jo Swinson for that period, on no fewer than 21 days – a majority – were there pieces devoted to the Coalition, austerity, or Jo Swinson’s voting record. What is worse is that on every single one of the eight days leading up to election day, there was at least one national media piece on this theme.

From the list of those media pieces below, you will see that the worst dates are 22 November, 4 December and 9 December 2019. It is no coincidence that these are the days after the most significant media appearances by Jo Swinson – the BBC Question Time special, the Andrew Neil interview, and the Channel 4 debate. And within the BBC Question Time special, of the 14 questions asked to Swinson, a majority (8) were about the Coalition, her voting record, and Lib Dem trustworthiness as a result.

Far from being a break with past elections, the scant coverage of the Liberal Democrats in the national media consisted of almost wall-to-wall coverage of questions about the Coalition and austerity, hitting its peak in the immediate run-up to polling day. Some will say that this wasn’t the only issue we were skewered on, and it is true that there were also pieces about our Stop Brexit pledge, and about the claim that Jo Swinson could become Prime Minister. But it must be acknowledged that the Coalition did not go away, and our failure to satisfactorily answer questions on the issue opened us up to a media onslaught which will have reached voters and will have coloured their opinions of our party. The combination of the three factors (Brexit, presidential campaign, Coalition) made us look worse than disagreeable – they made us look like a joke, and an irrelevance.

Furthermore, some will say that those members of the public who brought it up during national media events were merely “Labour plants” or “Momentum activists”. But even if they were (and there is scant evidence for this), that doesn’t mean that their questions weren’t damaging. By forcing us onto a defence of the Coalition on national television – one where we looked hypocritical, inept and untrustworthy, reminding voters of the biggest factor keeping them away in 2017 – we had no time to talk about the issues we were actually running on. And because of that, the media wrote another set of articles reminding voters of our past record on the very issues we were now campaigning on in the opposite direction. Such questioning and such coverage smothered our campaign – it gave the impression of an incompetent party, unable to answer questions satisfactorily or honestly, and under siege, in decline, and deflating. It was not an attractive proposition for voters.

Specific Objections

“Nobody I spoke to on the doorstep brought it up.” This is anecdotal evidence from the places you personally canvassed. And even if a voter doesn’t expressly bring up the Coalition, it doesn’t mean that their perceptions of our party as a whole aren’t influenced by how we deal with the question and by the way our response to it is reported in the media. Poor responses and the appearance of hypocrisy on any issue will always diminish us in the eyes of the voters.

“The only people who care are Labour hard-liners.” See the previous paragraph. Also, even if only Labour hard-liners bring it up on national television, it still means we have to answer the question, and answering unconvincingly will still make us look incompetent to all voters.

“The real problem is just that we don’t defend it enough.” Perhaps! But this doesn’t mean that the Coalition itself is not an issue which we need to have a response to. It is perfectly valid to think we just need to be more robust about defending it – I disagree with you, however. In the most recent polling by YouGov, the number one reason for 2010 Lib Dem voters not to vote for us anymore was because of the Coalition itself. And defending welfare cuts and austerity looks hypocritical for a party pledging to… overturn welfare cuts and austerity.

“Stop being so self-indulgent, this is such navel-gazing.” No, it isn’t, because as long as we keep getting questioned about the Coalition (which I believe will still happen, particularly if we don’t elect a non-Coalition leader this time), our responses to that question will have an impact upon how voters perceive our competence. It is absurd to think that voters assess our competence on every other issue, but somehow have no reaction whatsoever to a weak or unconvincing or apparently hypocritical answer about the Coalition.

“It’ll get brought up whoever is the leader.” I think this is true to an extent: but having a Coalition minister as leader makes the issue a very easy target, as we saw with Jo Swinson (and conversely, did not see as much with Tim Farron – during the entire 2017 election campaign, there were only three days where pieces about the Coalition were written, which is 67% less than in 2019). Furthermore, different candidates will be more convincing answering the questions about it. In my opinion, even if you think what we did in Coalition was good and don’t want to disavow it entirely, we can be convincing on the issue by having someone who was not part of it, and who doesn’t have a record of voting with the Conservatives, because they have no anchor dragging them back into the discourse about it.

Conclusions

The national picture matters. If our national campaign goes wrong, voters quickly pick up on it, and it leaves our local campaigners simply carrying out damage limitation. We did not go from first place to 11% between May and December because our activists suddenly put in half the effort. It was because of failings in the national campaign which made voters unwilling to trust us with their vote.

If the national picture matters, we have to examine what went wrong in 2019. Part of it was the presidential-style campaign; part of it was our Stop Brexit message. But with Coalition articles present on most days throughout the campaign, and dominating our coverage in the last week; with most of our set-piece media appearances having a significant section about austerity and voting records; and with the last available polling evidence showing that former voters of ours are most repelled by the Coalition, it is surely impossible to deny that the Coalition is and was an issue.

Dismissing the issue as simply the preserve of hard-line Labour activists “who will never vote for us anyway” is a mistake, because elections are not just about persuading individual swing voters in doorstep conversations. I have shown that any negative impact upon the national campaign will hamstring us in our target seats. And whether we like it or not, opening ourselves up to the criticism of hypocrisy and of supporting austerity is to create such a negative impact for ourselves.

We have to get to grips with this issue. Part of the reason I am backing Layla Moran is because she does not have that Coalition voting record, and so will not be questioned as severely about it, as shown by a comparison of national media between 2017 and 2019. When she does get asked about it, I believe she will have a better response when the issue is put. But – and this is the important bit – even if you disagree with me on who to support in this leadership election, please at least acknowledge that how we deal with the Coalition’s legacy is something that matters and needs genuine discussion, rather than dismissing it as a non-issue we shouldn’t even bother thinking about.

APPENDIX 1: COALITION IN THE NATIONAL MEDIA, ELECTION 2019

Coalition articles

1 November 2019 [The Express]

2 November 2019 [The i]

2 November 2019 [Express and Star]

3 November 2019 [Sunday Post]

7 November 2019 [Vice]

9 November 2019 [The Mirror]

10 November 2019 [Daily Record]

13 November 2019 [TalkRadio]

15 November 2019 [PoliticsHome]

18 November 2019 [The Guardian]

20 November 2019 [The Guardian]

21 November 2019 [Gal-Dem]

22 November 2019 [Metro]

22 November 2019 [Mirror]

22 November 2019 [Scottish Herald]

23 November 2019 [The Times]

3 December 2019 [Metro]

4 December 2019 [Guardian]

4 December 2019 [BBC]

4 December 2019 [Independent]

4 December 2019 [Daily Mail]

4 December 2019 [The Scotsman]

4 December 2019 [LBC]

5 December 2019 [London Economic]

6 December 2019 [Guardian]

7 December 2019 [Guardian]

7 December 2019 [The Economist]

8 December 2019 [ITV]

8 December 2019 [Guardian]

9 December 2019 [Independent]

9 December 2019 [local newspapers, syndicated]

9 December 2019 [The Scotsman]

9 December 2019 [London Economic]

10 December 2019 [Express]

11 December 2019 [The i]

4 December was the day after being grilled on it by Andrew Neil

22 November was the day after the BBC Question Time special

9 December was the day after the Channel 4 debate

APPENDIX 2: COALITION IN THE NATIONAL MEDIA, 2017 ELECTION

27 April 2017 [The Guardian]

1 June 2017 [The Guardian]

7 June 2017 [The i]